3. 13. 2024

Anti-Poverty Organizing with Residents of Toronto’s Carceral Shelter System

Sid Jackson

for Voices 4 Unhoused Liberation

Voices 4 Unhoused Liberation is a group of activists with lived experience of poverty and/or homelessness and precarious housing, currently doing solidarity work at the Delta Hotel Shelter in Toronto’s Scarborough neighbourhood. We work closely with former and current Delta residents to address the carceral conditions of the shelter system and the many ill treatments residents endure: untrained and abusive staff, threats of service restriction, infestation, poor food, lack of housing workers, lack of accountability for staff-caused harms, and more. The shelter system is a site of ongoing traumatization and debilitation leading to premature death.

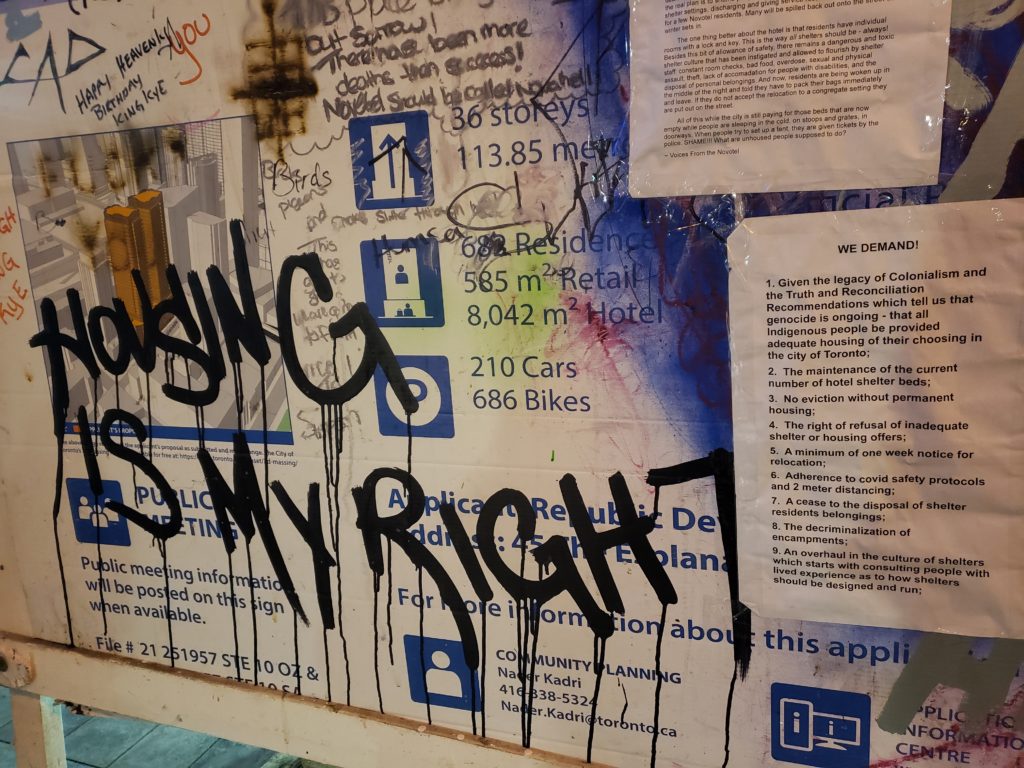

Voices 4 Unhoused Liberation started as a campaign within the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) to support residents at the Novotel shelter hotel when it was closing down. Our presence as witness to the brutal removal of residents from their homes, our connecting residents with media, and our occupation of the Novotel lobby to advance a set of demands catapulted the conditions of shelter hotels into the public consciousness. After the Novotel closed, we followed many of the residents as they were displaced to the Delta shelter hotel.

Like the Novotel, the Delta is run by the agency Homes First. It’s part of the temporary shelter hotel program that was initiated at the behest of activists during the COVID-19 pandemic, in response to how the shelter system’s infrastructure didn’t allow residents to physically distance from each other. Many unhoused people also moved to parks, establishing encampments where they could find safety in community and have greater agency over their lives. In response to the visibility of unhoused people in parks, the city attacked encampments with militarized police violence, while the city outreach program Streets To Homes tried to coerce folx back into the shelter system – sending encampment residents to shelter locations in the outer reaches of the city, far from the gentrifying downtown core. While the city was roundly critiqued for its heavy-handed police actions, its effort to clear encampments continues today.

Shelters in Toronto are supposed to be run according to Toronto Shelter Standards (TSS) and overseen by the Shelter Support and Housing Administration, a branch of the City of Toronto. While TSS speaks a language of respect, consultation, agency, and support, shelters remain carceral spaces of warehousing, control, punishment, and abuse. The demographic make-up of shelter workers is complex: the shelter industry is growing and becoming increasingly racialized. Labour conditions at the Delta are characterized by low pay and casualization; 90% of the unionized Homes First work force rejected a recent contract offer by the employer. Poor training is also a serious issue. While individual workers may have differing personal attitudes, skills, and empathies, they must do their jobs as dictated by Homes First management, and this involves causing both personal and structural harm to unhoused people. Social work as a discipline plays a role in maintaining the carceral violence of systems that manage the “care” of vulnerabilized populations, and these workers are incorporated into it. Such incorporation is part of poor people’s political-economic experience within global structures of class, race, and capital.

Without downplaying the challenges we face, Voices is committed to doing all we can to centre unhoused people and build collective power as we work across social differences and relative privileges. We also face the regular forced displacement of community members, which hinders poor people’s organizing. Under these conditions, Voices’ tactics include community-building via the redistribution of material necessities; case-work pursued through weekly Out-Reach (OR) sessions; collective production of knowledge about unhoused people’s social condition; symbolic interventions into broader social discourse; and resistance strategies that include direct action.

Building Community – Fighting Carceral Control – Confronting the City

Voices’ work is structured around weekly Out-Reach sessions, where we offer snacks, fruit, beverages, and other necessities including hygiene products, harm reduction supplies, winter gear, and underwear. We provide a selection of “know your rights” literature, developed according to residents’ expressed informational needs. As residents have taken ownership of OR, it has become a space of community building and information sharing about the issues they face. Through those conversations, Voices has built campaigns such as a successful petition to make Homes First meet its Toronto Shelter Standards obligation to hold monthly residents’ meetings.

At OR, we hear individual accounts of shelter abuses. In these instances, Voices does “case-work”: documenting complaint forms and corresponding with shelter management to seek a resolution. Most case-work involves supporting individuals facing “service restrictions,” the common practice of evicting people from a shelter because of a “rules violation.” According to TSS, service restrictions should be given only when a resident poses an immediate danger to staff or other residents. In practice, service restrictions are meted out in arbitrary ways. Former Delta resident Monark Desai received three restrictions for very minor incidents: throwing a ball at a friend in jest, helping a neighbour carry a TV to their room, and demanding staff respect his physical space by putting out his hand. In one instance, Star Security staff held him in handcuffs for hours, resulting in injury to him. As is common, shelter staff called police on multiple occasions to enforce those service restrictions, and ultimately Monark was permanently banned from the Delta Hotel. Shelter evictions result in lost and stolen belongings, lost jobs, harms to physical and mental health, disconnection from vital community, criminalization, violence from police, and even death. Service restriction case-work resists those abuses and responds to the fundamental human need for shelter.

Shelters maintain discipline mainly through the constant threat that residents will lose their beds. Confronting service restrictions exposes the procedural failures of a system that depends on isolating and punishing residents, preventing them from advocating for themselves. As abolitionists, we at Voices believe that shelter workers should be trauma-informed and practise de-escalation, conflict resolution, and transformative justice methods instead of the carceral and criminalizing techniques on which they currently rely.

On a structural level, service restrictions play an important role in the continual forced displacement of unhoused people, a practice that especially impacts people with disabilities. In the context of an affordable housing crisis, the years-long waiting list for rent-geared-to-income housing results in the shelter system turning away around 300 people a night, while the city’s intolerance of encampments means individuals are forced back into shelters. A key way beds are made available in the shelter system is by driving residents out through service restrictions – back onto the streets, where they are criminalized.

To address the constant displacement of the unhoused community and the barriers this poses to political organizing, Voices launched its No Homeless Evictions!! Campaign in late 2023, demanding a City of Toronto moratorium on shelter, encampment, and low-income housing evictions. The campaign includes engagement with shelter and encampment residents, defence strategies (such as case-work), public education, an open letter to Toronto mayor Olivia Chow, lobbying city councillors, and direct action. The campaign is part of a long history of activism that has called on Toronto’s city council (and other government bodies) to declare homelessness a national disaster. It’s in alignment with Shelter and Housing Justice Network’s winter plan, and with Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union demands that were delivered to the public on National Housing Day. Voices sees the No Homeless Evictions!! campaign as a struggle against the settler-colonial capitalist organization of the city and the police who protect it.

Poor People’s Revolution

Poverty is not simply an outcome of settler-colonial capitalism, but integral to it. Private property creates the conditions by which people become dependent on an employer for their livelihood. Traumatic life events, along with work conditions including precarity and underemployment, can lead to debilitation and wagelessness. Indigenous, Black, disabled, queer, and trans people, along with women, are disproportionately those who experience poverty; we are pushed to the lower end of the labour market or out of it altogether, while we’re busy doing undervalued social reproduction work for our communities to survive. Providing rent-geared-to-income housing is more cost-effective than the state’s carceral approaches to managing the poor, but poverty must be painful so fear of destitution will keep workers docile in the face of a plummeting standard of living. Thus poor people are funnelled into institutions that warehouse, control, and punish them.

Voices 4 Unhoused Liberation aims to open a chapter in every shelter in Toronto. We support the agency of unhoused people to bring their own critical issues to bear on public and left discourse. Unhoused people must be centred in the transformation of the shelter system, how encampments are managed, and social housing design. A poor people’s revolution means moving away from the oppressive wage labour and private property relations of settler-colonial capitalism and the carceral institutions on which these systems depend, and towards a society that prioritizes redistribution and sustainability: care, not profit.

Photo: Sid Jackson

Sid Jackson (They/Them) identifies as an uninvited guest of Scottish settler ancestry living and working on stolen Indigenous territories, as queer, non-binary, and mad. Jackson’s lived experience of poverty has led them into long time commitment to activist and creative work with poor, criminalized, and unhoused community, focusing on the carceral continuum of institutions that contain, control, and punish them. See their work at: carceralcontinuum.ca.

Related:

- Moments of Vast Possibility Solidarity Winnipeg’s Jesslyn Best and Leslie Ep discuss utopias, popular uprisings, gender and sexual freedom, communist politics, and speculative fiction with M.E. O’Brien and Eman Abdelhadi, the authors of the new book Everything For Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052-2072.

- What We Mean by Community is Our Yearning for Communism M.E. O’Brien on family abolition and the communizing of care as political horizons worth fighting for. A conversation with Midnight Sun editor David Camfield.

- Protest & Pleasure: A Revolution Led by Sex Workers A conversation with Monica Forrester, Toni-Michelle Williams, and Chanelle Gallant about why trans women of colour sex workers are the leaders we need, lighting the way to revolutionary horizons.

- Festivals of the Possible Megan Kinch on the Occupy movement, which erupted 10 years ago: its particular blend of spontaneity, organization, and technology; the forms it took in Toronto and elsewhere in Canada; and its mixed legacies. A personal and political reflection.